The Dance Troupe Teaching Dabke—and Cultural Survival—in the Diaspora

By Ragad Ahmad

August 15, 2025

In October 2023, as the El Funoun Palestinian Popular Dance Troupe in Ramallah followed the unfolding crisis in Gaza, the very act of celebration—the foundation of their artistic mission—felt like betrayal. How could they ask audiences to clap along to traditional wedding songs while families were mourning their dead?

The troupe collectively decided to suspend their public performances in Palestine indefinitely, for several practical and emotional reasons. Mobility had become severely restricted within and outside Palestine, and the unthinkable violence in Gaza was taking place just 83 km from their rehearsal space. But they continued their essential work of production and cultural development—a distinction Noora Baker, El Funoun's Head of Production, emphasizes as vital to understanding their mission.

"The El Funoun troupe doesn't perform for ego or artistic fulfillment—they perform for their people and their land,” says Noora Baker, El Funoun's Head of Production. Photo: Ahmad Talath

The choice came not from defeat but from a reckoning with what it means to cultivate and display art during catastrophe. "We don't do art for the sake of art—it has a meaning and a purpose," says Baker, whose experience with the organization mirrors the troupe's journey from cultural ambassador and producer to something more urgent: cultural lifeline.

So in 2023, El Funoun's 267 volunteers—dancers who had spent countless hours perfecting dabke’s intricate footwork and synchronized movements—found themselves with a new priority. Instead of dancing for audiences, they would focus on teaching communities, particularly those scattered across the diaspora, how to keep Palestinian traditions alive themselves.

Baker articulates this delicate balance as someone who has spent decades navigating it within an organization that has maintained its vision since its founding in 1979. "The El Funoun troupe doesn't perform for ego or artistic fulfillment—they perform for their people and their land,” she says. When those people face an existential threat, the performance itself must evolve.

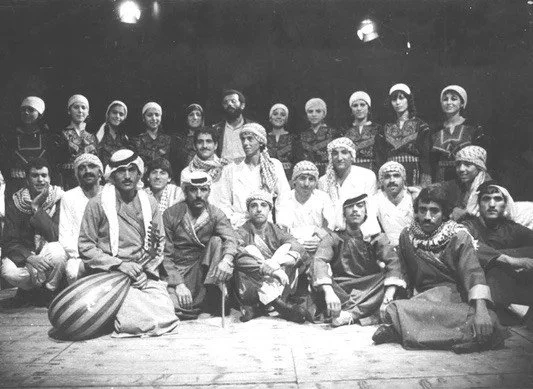

The El Funoun troupe in 1984, Birzeit. Photo courtesy of El Funoun

This understanding of culture as inherently political isn't new for El Funoun, but recent events have sharpened its focus. For nearly five decades, the organization has understood that keeping Palestinian tradition alive and building upon it constitutes a political act in a context where Palestinians’ very existence remains contested. Every dabke step, every traditional song, becomes an assertion of continuity in the face of erasure.

El Funoun now works to bridge the growing chasm between Palestinians living under the occupation and those scattered across the diaspora. Baker describes this as "working against a world designed to separate Palestinian communities from each other and from their homeland." This month, as part of their Tawasil program—literally translating to "drawing closer" in Arabic—El Funoun will host dabke workshops with Al-Bustan Seeds of Culture in Philadelphia.

Samer Karajah, a 29-year-old choreographer, first began dancing dabke with the Handala Dabke Troupe in his village of Saffa before joining El Funoun in 2010. These days, he teaches dabke in New York, where he has witnessed firsthand the way Palestinians’ relationships with their culture differ depending on where they live.

For Palestinians living in the homeland, cultural practices are embedded in the rhythm of ordinary existence. Dabke is a natural part of weddings, celebrations and other community gatherings, and traditional songs accompany daily life. But what happens organically in Palestine requires intention and effort abroad. Palestinian families in the diaspora must actively seek out opportunities for their children to learn traditional dances, songs and customs.

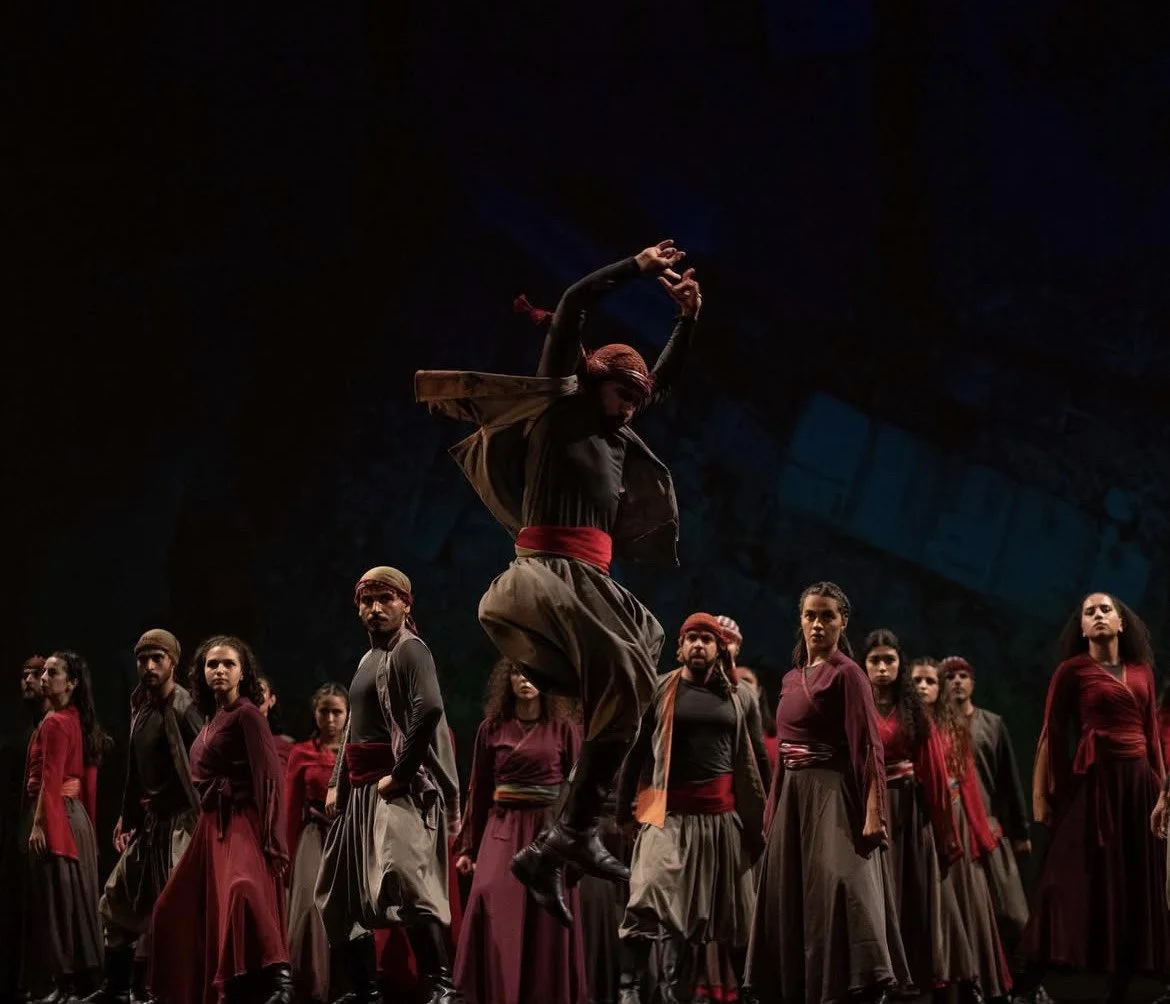

For nearly five decades, El Funoun has understood that keeping Palestinian tradition alive and building upon it constitutes a political act in a context where Palestinians’ very existence remains contested. Photo: Ahmad Talath

It is this hunger for authentic cultural connection that El Funoun is responding to when they partner with cultural organizations in the diaspora. Fatmeh Bahhour is the co-founder of Sawa SoCal, a nonprofit dedicated to Palestinian cultural education based in the Los Angeles area. According to Bahhour, Sawa SoCal chose to collaborate with El Funoun in 2024 for an in-person workshop specifically because of the troupe’s traditional approach.

“There's particular credibility and value in learning from Palestinians still living on the ground," Bahhour says.

Sawa SoCal’s collaborations with El Funoun now include remote instruction that connects Palestinians across continents. Master teachers in Ramallah transmit knowledge to dozens of students throughout California, creating virtual bridges that span vast distances while maintaining cultural authenticity.

El Funoun’s pedagogical approach recognizes something fundamental about cultural preservation: it's most effective when it becomes distributed rather than centralized. Each participant who learns traditional techniques through these workshops becomes a potential teacher, creating a multiplying effect that extends cultural knowledge far beyond formal programming. Children carry their knowledge home to siblings and parents. Community members who master traditional songs become resources for future celebrations and ceremonies.

As El Funoun prepares for their Philadelphia workshops, Baker notes the resonance between past and present struggles. Palestinians connect with folklore music and dance from the 1980s not only for nostalgic reasons, but also because the settler colonialism that these forms of cultural expression were working against still continues today.

It is this sense of continuity that gives the troupe's current work its particular power. They're not just teaching dance steps or preserving abstract traditions—they're sharing tools for community building and resistance that have sustained Palestinian communities for decades. When dancers link arms in dabke, they form chains that require coordination and trust—an apt metaphor for broader solidarity, and a way of practicing collective resilience in miniature.

As Baker explains, "This history and movement brings people together and carries the messages of working together and belonging." And in moments when Palestinians worldwide might feel isolated or powerless, the workshops provide a tangible connection to ancestral practices of survival and solidarity.

"We can feel so helpless–until you listen to the same music and dance the same dance our ancestors did against the occupation to survive.”

***

Ragad Ahmad is a Palestinian–American Muslim born and raised in Philadelphia. She currently studies Peace and Conflict Studies at Swarthmore College, where she explores issues of decolonization and climate justice.