Art as Resistance | Philadelphia Potters Carry Palestinian History and Heritage Through Ceramics

By Lauren Abunassar

February 2, 2026

In 1998, renowned Jerusalem-based ceramicist and art-historian Vera Tamari took to the shores of Jaffa with a set of hand-sculpted ceramic faces. She attached the faces to iron rods and planted them in the sand, watching them sway slightly in the wind, the waves visible through the eyes and mouths cut into the clay.

The faces, part of a project that would be known as “Oracles of the Sea,” were modeled after the faces of Tamari’s ancestors, Palestinians temporarily displaced to Jaffa following the 1948 Nakba. Taking their ceramic renderings to Jaffa was a way for Tamari to create what she later described as a living memorial. Her use of clay — the medium she’d become known for — added a further layer of meaning. “Clay is malleable, still-forming material that solidifies into something unbreakable," she said. In other words, working with clay could serve as a poignant symbol of endurance.

Today, Philadelphia-based artist Amal Tamari follows in her great-aunt’s footsteps. A trained ceramicist whose work sits at the intersection of beauty and function, Tamari thinks deeply about how to offer insight into Palestinian heritage, culture and history through clay. “I think ceramics, especially functional ceramics, is an amazing form of metaphor,” she said. “Ceramics hold things — food and liquid and memory. Ceramics come from the earth. You can dig ceramics and dig clay almost anywhere you are. So it’s sort of land-specific. It’s also a really intimate form. You put your mouth on it. You share food with your loved ones with it. It’s different than having a painting on a wall.”

When she was in high school, Tamari visited Hebron, the West Bank city renowned as a center for traditional Palestinian pottery dating back to the fourth century B.C.E. The experience of seeing the famed ceramics and blown glass sparked her interest in the functional beauty of Palestinian craftwork. She went on to study ceramics at Earlham College, followed by a fellowship at the Penland School of Craft. She now holds an Associate Artist position at the Clay Studio in South Kensington. And her work often embraces some of those designs she saw in Hebron: colorful, deeply symbolic and unabashedly domestic, bowls, vases and pots painted with Palestinian irises, pomegranates, olives.

Tamari has built intricate vases that she paints with vibrant illustrations of other, equally intricate vases. She has painted tiny homes on the borders of some of her own pots and plates. She has made a chair with inlaid tiles hand-painted with strawberries, Jaffa oranges, windows and keys — images that convey both memory and home.

“I find I’m especially drawing keys all the time,” she said. After all, the key is a classic symbol of the Palestinian Right of Return. Making use of images like these is a way for Tamari to not only find beauty in ordinary objects, but to excavate their nuanced symbolism. As Israel’s genocide in Gaza continues, this project feels all the more urgent to her.

“I was always referencing my heritage and Palestine in my work, but it’s a lot more explicit now, post-October 7th,” Tamari said. “I feel there is more urgency now to be more specific with my work. To have a message. I understand the feeling of being too burdened by grief to make. But for me, the impulse to be making constantly connects me to things that feel beyond my reach.”

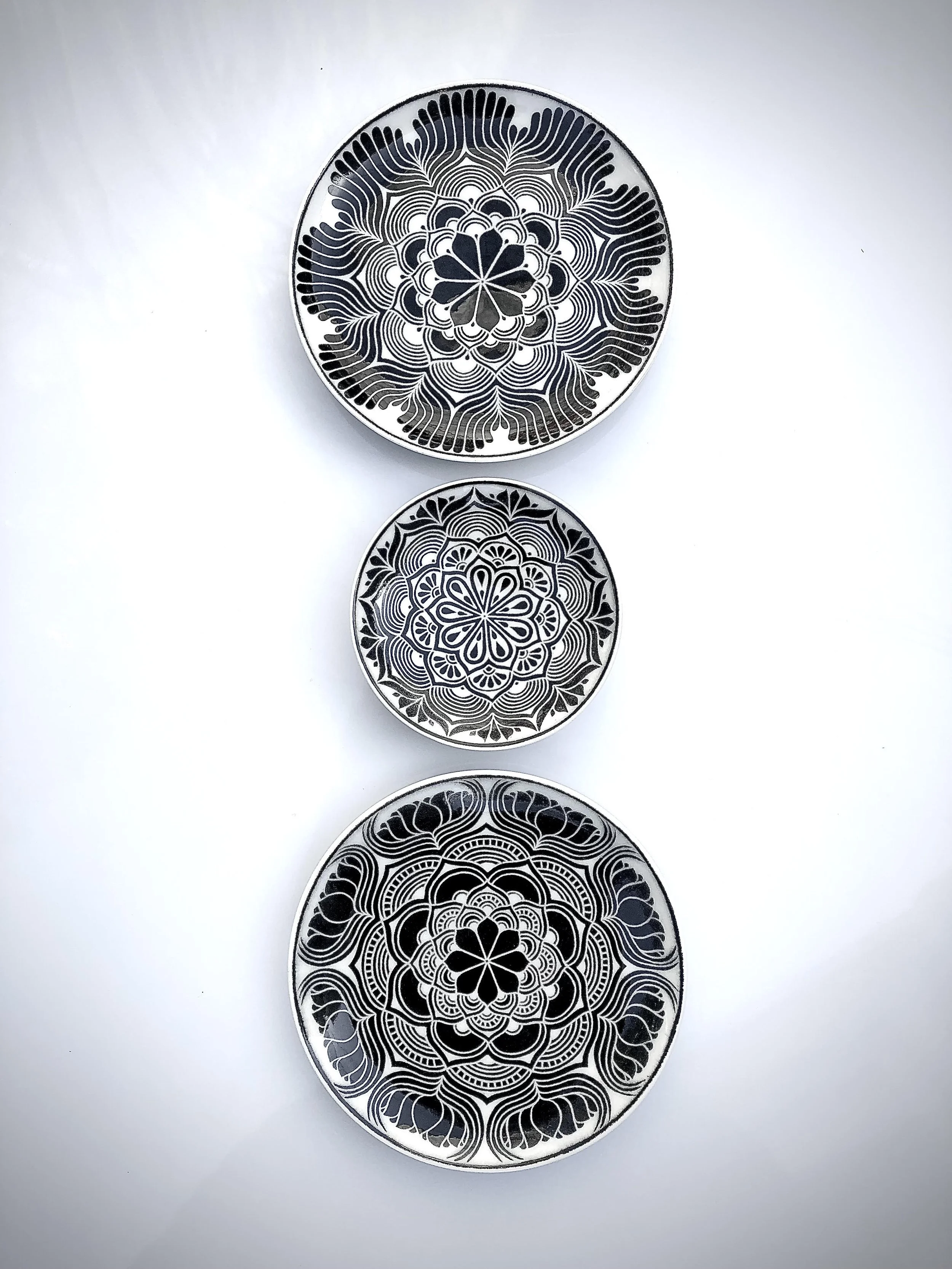

A selection of works by ceramicist Amal Tamari, who discovered a love of Palestinian craftwork on a visit to Hebron while a high–school student. Top: A collection of tableware. (Photo by Amal Tamari) Middle: “Tiled to Ramallah” (Photo by Sophia Greeson) Bottom: Key Plate. (Photo: Penland Gallery)

Another source of grounding for Tamari has been fusing her artistic practice with her advocacy. A dedicated member of Potters for Palestine, an international grassroots effort to bring clay artists together in support of Palestine, Tamari’s work has been able to auction off her artwork to benefit mutual aid groups in Gaza. She has also been inspired to curate a ceramics show featuring Palestinian artists, set to coincide with the 60th-annual conference of the National Council for Education on the Ceramic Arts this March. Tamari’s show will be held at the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

Being surrounded by Palestinian community members and the trappings of a rich artistic history has motivated her to continue creating. “When I first started making work, I was in a stage of my life where I was afraid to not be at home, and where I had a lot of anxiety in general,” she said. “But I think that’s changed a lot. Now, I’m thinking about Palestine and what it means to not have been able to ever live there or even go there often. I think about all these people who don’t have homes anymore. And yet, people in Gaza are still making ceramics. So my own practice has gotten a little bigger than myself.”

Another Palestinian American, Philadelphia ceramicist Angela Humes, has a similar understanding of how her work sits in a larger context of craft and survival. “I have a tendency to name my pieces after women in my family, embodying and embracing their intrinsically radiant spirit,” Humes said. Like Tamari, Humes grew up surrounded by family art: elaborate sculptures and tapestries, ceramics and paintings, her Teta’s embroideries of olive trees, camels and dizzying patterns. Like Tamari, Humes finds her own practice fueled by a desire to make work that is not just beautiful and symbolic of her heritage, but useful.

She hand-draws all her designs so that none of her patterns repeat more than once. And she frequently uses a black-and-white color palette — evoking an early passion for black-and-white photography. “At a young age, my dad, who was always very interested in photography, put a camera in my hands along with an issue of “National Geographic.” It clicked. I wanted to be a photographer. I wanted to be Vicki Vale from ‘Batman,’” Humes joked. And when her mother chaperoned a middle school field trip to some local artist studios, the feeling of fate clicked again.

“There was a man giving a wheel-throwing demonstration. He started with a huge lump of clay and threw it up and up and up into a cylinder that was taller than his arm. My young brain interpreted it as magic. I knew that I needed to learn this magic.”

Today, Humes continues to throw her own ceramics and teaches others to do the same as an instructor at the Abington Art Center. Her work has been a way to create a visual record of her experiences as a first-generation Palestinian American. “I’ve learned that others don’t know much about Palestinian history,” Humes said. “I’m happy to put work out in the world that can show others about the deep, rich, intricate beauty of the culture.”

Angela Humes credits her frequent use of black and white in her ceramics to an early interest in analog black-and-white photography. Above, a vase (top), hand-painted cups (middle), and a plate (bottom) made by Humes. (Photos by Angela Humes)

In 2024, this pursuit took on new meaning when Humes was approached by Nickelodeon to create a Nickelodeon-themed artwork to celebrate Arab Heritage Month. “I grew up on Nickelodeon so I felt like my life had come full circle, and I was so excited!” Humes said of the somewhat surreal experience. “The piece I made had Nickelodeon colors and slime, of course. And then I had my traditional motifs showcasing the iris, since it is the flower of Palestine. I was honored and grateful to have been asked to do that project because I got to show a younger generation some of the beauty of Palestinian culture.”

Like Tamari, Humes is drawn to the way ceramics, as a medium, embodies heritage not just in its decoration but in the process and materiality itself. “I feel all art and mediums hold cultural, emotional and symbolic meaning. But ceramics specifically show us this in the material used (clay body, slips, glazes), shape, surface decoration, and, most importantly, through touch,” Humes said.

“All handmade ceramic art has the touch of the maker, and it can be seen through throwing lines, finger prints, the flair of a rim or foot… It can represent the maker’s emotional intention if you can recognize fast hand movements (which determine the thickness or thinness of walls) or if you can recognize intentional time spent slowly on intricate or precise designs. By looking at material or tools used, you can see if a piece is modern or ancient… All of these aspects speak to cultural, emotional and symbolic references that help us see the walk this piece has taken through life from its creator.”

Historically, traditional Palestinian ceramics have been especially well suited for the cultural archive, given their role as both ornament and instruments for daily life — bowls for eating, jars for storing, tiles for cooling homes, vessels shaped by and for use. That usefulness is precisely what has allowed pottery to carry narrative across generations, even as borders, access and archives have been disrupted. It is also what has led cultural institutions to fight for the protection of traditional Palestinian ceramics.

At the end of 2025, UNESCO announced an open call offering grants to support the preservation and revitalization of endangered traditional crafts in Palestine, naming pottery among those most at risk. The designation gestures toward the importance of keeping traditional ceramics alive not just for their artistic value, but for how they embody Palestinian history and survival. There are few better examples of this than the huge resurgence of handmade pottery in Gaza, where shortages of basic tableware have encouraged Gazans to return to ceramics out of necessity.

For Tamari, this understanding of clay as a feature of daily life is not theoretical, but lived — shaping how and why she makes. “I’ve been wondering a lot lately, why do we write things down?” she said. “And I feel like the answer is, because it creates a record. It says something. And art like ceramics also says something, maybe in a way that makes it easier for people to take in.”

Like Vera Tamari’s faces planted in the sand at Jaffa, Palestinian ceramics today continue to look outward — toward memory and loss, toward what persists. The ceramic objects made by artists like Amal Tamari and Angela Humes are shaped by a similar openness: work meant to be touched, used and carried forward. In this way, clay is not just a record of Palestinian history, but a belief that it will live on.

***

Lauren Abunassar is a Palestinian-American writer, poet and journalist. Lauren holds an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and an MA in journalism from NYU. Her first book, Coriolis, was published in 2023 as winner of the Etel Adnan Poetry Prize. She has been nominated for a National Magazine Award and is a 2025 NEA creative writing fellow.

Al-Bustan News is made possible by Independence Public Media Foundation.