Cinema, Etcetera | “One Battle After Another” and the Vanishing of Revolutionary Arab Cinema

By Joseph Fahim

October 16, 2025

In a year that has been largely dominated by political upheaval, few Hollywood films have been as hotly and widely debated as Paul Thomas Anderson’s action comedy “One Battle After Another.” Celebrated by the left and derided by the right, “One Battle” is the picture of the moment: the rare, unabashedly political Hollywood blockbuster that has seized the cultural discourse in a manner that has not been seen in more than a decade.

Front and center in Anderson’s highest grossing film to date are mutiny, the burning desire to change the status quo and the legitimacy of the radical left’s use of violent resistance. The popularity of the film compelled me to ask the most obvious question in relation to Arab cinema today: where did our angry, rebellious films go?

Teyana Taylor as Perfidia in “One Battle After Another,” 2025. ©Warner Bros

Loosely based on Thomas Pynchon’s 1990 novel, “Vineland,” the film stars Leonardo DiCaprio as Bob, a former member of a radical left group that disbanded after his ex-partner, Perfidia (Teyana Taylor) was forced into an ill-defined, peculiar affair with Col. Steven J. Lockjaw (Sean Penn), a self-hating white supremacist obsessed with Black women. Sixteen years after the dissolution of the unit, Bob and his teenage daughter, Willa (Chase Infiniti), find themselves on the run when Lockjaw discovers their whereabouts.

Subplots include Benicio Del Toro as Sensei Sergio St. Carlos, community leader and Willa’s karate instructor, who toils to evacuate undocumented immigrants from the clutches of an ICE-like law enforcement unit led by Lockjaw. An ultra-right secret society called the Christmas Adventurers Club invites Lockjaw to join their crusade to purify America of its non-white population, but first he must undergo a fateful background check that will divulge long-suspected secrets from his past.

Breathless action, wry stoner comedy and a spectacular car chase are elements of what is essentially a father-daughter relationship story set against a racially volatile climate that eerily echoes present-day America, particularly in the scenes of immigration raids.

Although references to Covid and to personal pronouns suggest that the film takes place in the current decade, the relative atemporality of the drama and the absence of allusions to real historical events implies that this grand American malaise — racial, social, economic — precedes the second Trump term. Anderson does not attempt to diagnose the roots of America’s epidemic discontent, but he does underline the brokenness of a system ravaged by capitalism and racism.

Leonardo DiCaprio plays Bob, a perpetually stoned former revolutionary. Still from “One Battle After Another,” 2025. ©Warner Bros

While some commentators have criticized the film’s vague position on violent resistance, the director of “There Will Be Blood” (2007) and “The Master” (2012) hints at a fundamental truth behind every failed revolution: without an organized grassroots movement, without political backbone, uprisings are destined to fail. In that sense, “One Battle After Another” is not just about the U.S. — it’s a fable about the failure of the left worldwide. And for the Arab viewer, it’s impossible to watch the film without drawing comparisons to our own failures in the Arab Spring.

Watching Anderson’s political parable unfolding on the world’s biggest screens has been undeniably cathartic, a recognition of our frustrations and feelings of helplessness. Like Bob, the left, in all its various shades, has been stranded in a haze of defeatism and impotence for decades, only to be jolted now by a violent new world order devised by leaders hellbent on reshaping their countries in their own image.

The revolutionary charge of “One Battle After Another” — especially its defiant ending — is precisely what has been missing from post-Arab Spring cinema. Civil disobedience has never been an integral part of the DNA of Arab cinema. The anti-imperialist sentiment of early Arab films was always aimed at former European colonizers, not their own authoritarian rulers. Due to pervasive censorship, Arab filmmakers primarily engaged with their leaders via subtle criticism, but they rarely went as far as to entertain the possibility of a revolution.

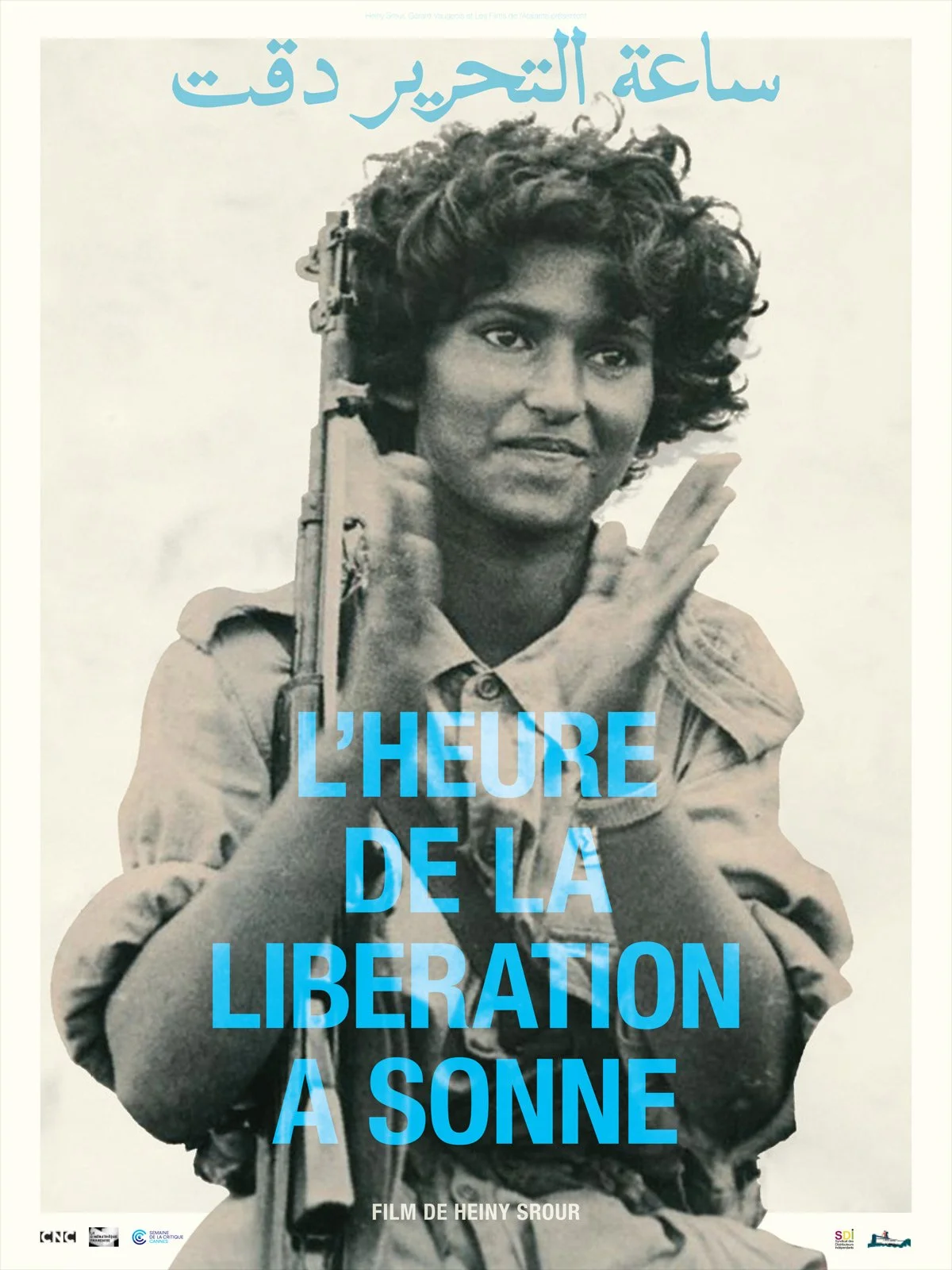

There were a few exceptions to the rule. Veteran Lebanese filmmaker Heiny Srour constructed a small but remarkable oeuvre founded on stories of Arab rebels: the Omani women insurgents of “The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived” (1974); the Lebanese and Palestinian female freedom fighters of “Leila and the Wolves” (1984); and the great Egyptian composer Sheikh Imam in “The Singing Sheikh” (1991).

What set Srour’s films apart is not only the steadfastness and insubordination of her protagonists, but also the incredible lengths she went to, to realize her envelope-pushing vision.

Egyptian cinema also toyed at times with imagined uprisings, always formulated as allegories. Released in the aftermath of defeat in the Six–Day War in 1967, Hussein Kamal’s brooding folktale “Shey min el khouf” (Some Kind of Fear, 1969) depicts a village rising up to dethrone its thuggish ruler — a clear stand–in for Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Poster of Lebanese filmmaker Heiny Srour’s 1974 film “The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived.” ©Srour Films

Decades later, in the early 90’s, veteran screentwriter Wahid Hamed teamed up with director Sherif Arafa and actor Adel Emam — the Arab’s world biggest comedy star — for a series of political dramas. The greatest of the films, “Al-irhab wal kabab” (Terrorism and Kebab, 1992), was an acerbic satire about a middle-class engineer who accidently holds the country’s former central administrative building hostage before banding together with a diverse group of workers to demand that the government step down.

The revolution-themed pictures released in the wake of the Arab Spring reflected the upbeat mood of the time; their defiance was directed at political establishments that had since been unseated.

Few, if any, Arab films — made by Arab filmmakers, inside the Arab World — over the past decade have dared to entertain the possibility of rebellion against an incumbent autocracy, far more oppressive than Anderson’s America.

Limited funding opportunities in the Arab world and the rise of Saudi Arabia as the biggest, most lucrative market in the region have coerced filmmakers into submission. In order to sustain a living in cinema and vie for the big commercial opportunities, Arab filmmakers have chosen to water down their stories. They opt not to offend, not to provoke, not to challenge. Fury, seditiousness and recklessness have been replaced by Disney-like yarns about friendship, patriarchy, marriage and quirky familial relationships conceived in the benign style of social realism.

There are remarkably honest, intellectually rich Arab movies being released every year, even in mainstream genres. But if the success of “One Battle After Another” has shown us anything, it’s that Arab cinema must fight harder for the freedom to make revolutionary films.

***

Joseph Fahim is a film critic, curator and lecturer. Currently Al-Bustan’s film curator, he has curated for and lectured at film festivals, universities and art institutions in the Middle East, Europe and North America. He also works as a script consultant for various film funds and production companies; has co-authored several books on Arab cinema; and has contributed to news outlets, including Middle East Eye, Middle East Institute, Al-Monitor and Al Jazeera. In addition, his writing can be found on such platforms and publications as MUBI’s Notebook, Sight & Sound, The Criterion Collection, British Film Institute and BBC Culture. His writings have been translated into eight different languages.

Al-Bustan News is made possible by a grant from Independence Public Media Foundation.