For Tazhib Master Ayse Tunc, Illumination Is the Art of Slowing Down

By Gawhara Abou-eid

December 19, 2025

“Muradiye Complex in Bursa,” 2011, by Ayse Tunc. All photos courtesy of the artist.

Ayse Tunc did not set out to become a master of Islamic illumination, known as tazhib, but her lifelong love of drawing naturally led her there. Growing up in the small Turkish city of Sivas, she filled private notebooks with detailed drawings of flowers and natural motifs, carefully imitating what she saw while letting her imagination roam.

“I always had a special private notebook. I was writing and drawing. I was very romantic,” Tunc says.

As a child, she balanced playtime with long, solitary hours spent drawing, an early sign of the patience, precision, and stillness that would later shape both her artistic practice and her approach to life.

That relationship with drawing eventually led Tunc, unexpectedly, to tazhib (or tezhip in Turkish), a centuries–old art form defined by intricate floral and geometric patterns, precise linework and gilding with gold leaf. A family member suggested she explore the field and, despite being a complete novice, she took a highly competitive university talent exam without preparation — and passed.

“Many people were working for years for this exam, but I didn’t have any preparation,” she says. “Still, I passed.”

Tazhib artist Ayse Tunc works on a sketch.

Included on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity list, tazhib originated in the Sassanid era of pre-Islamic Iran (then Persia) and flourished after the advent of Islam in the seventh century, when figurative depictions were largely prohibited. Practiced across Turkey and Central Asia, tazhib adorned Qur’anic manuscripts, literary texts and miniatures. Today, cities such as Konya in Turkey, celebrated for its spiritual and historical heritage, remain vibrant centers of the art, where it is taught in universities, private studios and workshops.

According to UNESCO, women play a prominent role in preserving, teaching and transmitting the art across generations. It was within this enduring tradition that Tunc pursued her formal studies at Konya’s Selçuk University’s Faculty of Fine Arts.

Completing both undergraduate and master’s degrees, she focused her graduate research on 16th–century Qur’anic tazhib manuscripts housed at the Mevlana Celaleddin Rumi Museum. Tunc remained at the university for over a decade, teaching courses on tazhib pattern and tile design, and in 2014, she received her traditional tazhib ijazah, a master’s certificate authorizing her to practice and teach the art.

In 2018, marriage brought Tunc to Philadelphia, interrupting her doctoral studies and her artistic career. She gave up her university position, adapted to a new language and culture and devoted herself to raising her children. During her youngest daughter’s early infancy, she paused her daily artistic practice — a difficult adjustment.

“If you draw for many years nonstop and then suddenly stop, it’s very painful,” she says.

Above: “Sky” (Sema), 2011, by Ayse Tunc. According to Tunc, “the changing techniques, background patterns and colors mirror the ever-changing nature of a person, moving from one phase to another.” Below: Detail from “Sky” (Sema).

Gradually, she returned to drawing, first privately and then through commissioned work. Over the past few years, Tunc has rebuilt a full–time professional practice in Philadelphia, teaching online and in person, creating commissioned pieces and leading workshops at colleges and cultural spaces, including an upcoming four–part workshop series at Al–Bustan Seeds of Culture early next month.

She emphasizes that while mastering pattern design takes years of study, her workshops allow beginners to experience both the technical and meditative dimensions of the art. Tazhib may be rooted in Islamic tradition, but it resonates far beyond religious boundaries, she says.

“Life is so fast. When people do tazhib, they slow down. They find time to think about themselves.”

For beginners, tazhib presents a distinct mix of challenges and rewards. The most difficult aspect is working with the very thin brushes used for outlining, which demands intense concentration and a steady hand, Tunc says. “If you continue to breathe as you trace a line, your outline will get messy.”

In contrast, using tracing paper to transfer pre-drawn designs onto parchment allows students to focus on coloring and basic outlining without needing to understand complex design principles. In her workshops, Tunc emphasizes practice and patience, guiding students step by step so they can experience the discipline and the satisfaction of the ancient art form.

For Tunc, tazhib begins with careful attention to every line and motif, guided by close observation of the natural world — a foundation for her sketches and the delicate designs that emerge.

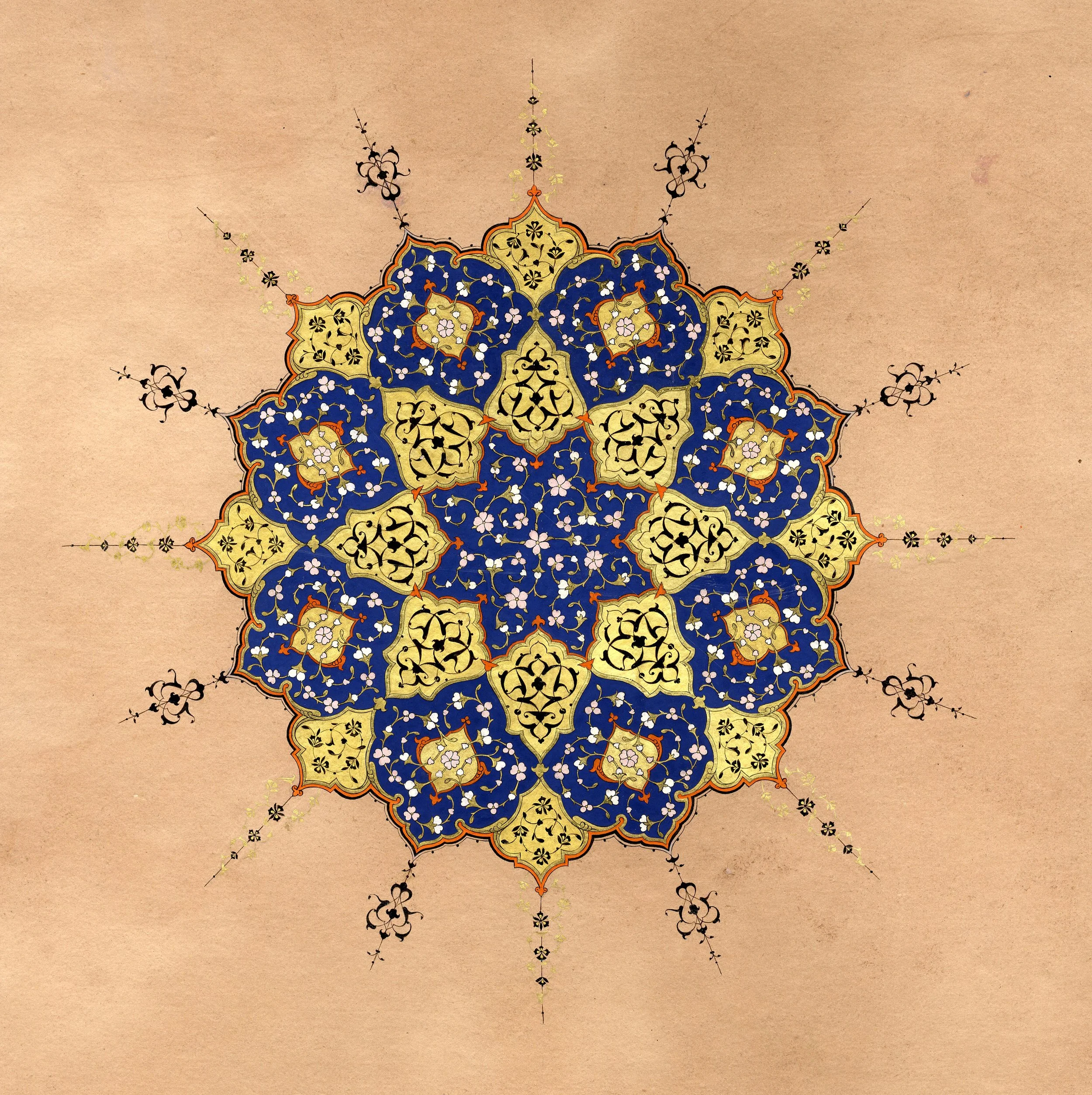

“Zahriye,” 2009, by Ayse Tunc, who describes the work as: "If Tazhib patterns were performing water ballet.”

Her own creative process begins with observation. Long walks through nature inspire her with the symmetry and harmony found in leaves and flowers, which she sketches before translating them into gold and watercolor on paper. Tunc’s practice is guided by classical rules, including çift tahrir, or double outlining, and the delicate shading known as halkâr.

That technical discipline is inseparable from the symbolism of the materials themselves, she adds, especially gold.

“It’s the most valuable thing in the world. Because the Qur’an is the most important book for Muslims, we use gold to show our honor and our respect… And [tazhib] comes from Arabic roots. It means ‘making or transforming something into gold’.”

Tunc also draws inspiration from early illuminated Qur’ans and historical manuscripts, admiring their repetition, intentionality and meticulous craftsmanship. Museum visits, particularly to Islamic art collections, continue to renew her creative energy.

When she first arrived in Philadelphia, Tunc often found herself explaining what tazhib was. Over time, exhibitions, commissions and workshops have created visibility and community around the art form. The city’s large student population and vibrant art scene, along with living in University City where her husband teaches at the University of Pennsylvania, have helped her rebuild a sense of belonging, she says.

Even after years of formal training and building a professional practice in Turkey and the U.S., Tunc’s approach remains rooted in the curiosity and wonder she felt as a child, captivated by the rhythms and forms of nature.

“Art is not just about practicing — it has meaning,” she says. “If people go deep [within themselves], they will find something meaningful inside it.”

Learn more and register for Ayse Tunc’s four–week Illumination Workshop series starting on Jan. 7, 2026 at Al–Bustan Seeds of Culture (310 W. Master Street).

***

Gawhara Abou-eid is an Egyptian-American researcher and journalist from Lewisburg, PA and an Al-Bustan News media fellow. They hold a BA in International Relations from The George Washington University, with a concentration in International Security Policy. Gawhara has published research for the League of Arab States in Cairo, and their journalism has appeared in The Standard Journal and The News-Item.

Al-Bustan News is made possible by a grant from Independence Public Media Foundation.