‘Iran is Not a Monolith’: Philadelphia Iranians Feel Conflicted Following Israeli and American Attacks

By Lauren Abunassar

July 3, 2025

Just a few days after Israel fired over 100 missile and drone attacks at Iran, killing over 600 and injuring over 4,500, Philadelphia-based Iranian Sanaz Yaghmai tried, once more, to call her father in Tehran.

“He is just a few kilometers from where bombs fell,” Yaghmai said. At the time, she was gathered with a group of local Iranian friends, turning to community to process news of the onslaught of attacks. They cooked together, danced together, discussed their fears. And then they sat together while Yaghmai called her father on video. She had been unsuccessful getting ahold of him before, struggling to break through country-wide internet blackouts and the chaotic aftermath of the attacks.

When he finally answered, she and her friends—most of whom had never met him before—watched as he did a 180-degree turn with his camera phone, surveying the accumulating damage from his balcony. “Smoke filled the horizon,” Yaghmai said, holding back tears. In that one turn of the camera, the group saw at least two sites Israel had hit, the blurry smudge of smoke and the skeletal remnants of explosions a harrowing reminder that Yaghmai’s father was close, very close, to the fallout from Israel’s brutal campaign for regional dominance.

“I have been studying and working with the refugee and immigrant community as a therapist,” Yaghmai said. “I’ve worked with people who have fled violence and war-torn countries. So I know the struggle from a more professional standpoint. But to see it, for the first time, happening literally and figuratively this close to home—my dad and my homeland—I felt like I was living in a nightmare.”

A few days later in Philadelphia’s Washington Square Park, Yaghmai and her nonprofit Philly Iranians hosted a potluck with other Iranians and allies, turning to community for hope and healing. From 6 p.m. to midnight, Iranians came and went. Much like Yaghmai’s gathering with friends, people cooked and ate and danced. The comfort of presence and of witness was clear. They didn’t have to speak about the ongoing atrocities, the regional fragility, the overwhelming helplessness that many Iranians are now grappling with.

Iranian-American therapist Sanaz Yaghmai at a hotel in Khur, in the Isfahan province, in 2015. Photo courtesy of Sanaz Yaghmai

Yaghmai, who has lived in Philadelphia since 2021, first came to the U.S. as a 17-year-old. Born in Dubai after her family fled the Iran–Iraq War that began in 1980, it has been nearly a decade since she last visited Iran. In 2022, Yaghmai co-founded Philly Iranians, a nonprofit dedicated to advocating for a free Iran. She joined the global wave of protests following the arrest of 22-year-old Kurdish Iranian Mahsa Amini by Iran’s morality police. Amini died in police custody, sparking the international Women Life Freedom movement, fighting for the end of all forms of discrimination and oppression in Iran and calling for the fall of the Islamic Republic.

For Yaghmai, co-founding Philly Iranians was a way to lend her might to the resistance of theocratic extremism in her homeland—and amplify Iranian voices and culture, defying the isolation that has held the Iranian diaspora in a chokehold for decades.

“Our isolation comes from the fact that nobody ever talks about the Iranian people,” Yaghmai said. “They talk about Iran as a country, oftentimes referring to the Islamic Republic dictatorship and what's good for the U.S. But in any of the public information that gets put out there, nobody ever talks about the people. And so a lot of people that I speak to are not only grieving what's happening inside Iran, we're also seeing more and more resentment towards the media that nobody ever gets our story straight.”

And the story is a deeply complicated one, full of what Yaghmai calls a volatile emotional spectrum of fear, anger and a very fragile store of hope that expresses itself in fleeting moments. “I have this frustration at the state of the world because [in addition to people who are mourning or afraid] I see people who are happy about the bombings—some of them family—because they say [Israel] is only targeting the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps or heads of police or whatever,” Yaghmai said.

“I don’t know if it’s denial or a coping mechanism where they’re trying to tell themselves they’re safe because Israel is only trying to kill certain people. But it’s the height of cognitive dissonance for people to believe that Netanyahu is a kind of savior [who will help usher in the end of the Islamic Republic regime].”

Yaghmai admits it is hard not to feel a hesitant hope that the regime’s vulnerability to attacks might signify its inevitable downfall. But she wonders how to express this hope without being cast as pro-war. While she wants the bombing, in no uncertain terms, to end, she also sees both sides of an argument where, on one hand, the Islamic Republic could be weakened in these attacks, and on the other hand, the civilian casualties and damage to infrastructure only erode the capacity to fight the regime from within.

It’s a sentiment echoed by Anoushé, another Iranian-American who asked that her last name be withheld to protect the safety of family in Iran. Though she was born in California, Anoushé’s father is from Karamabad, roughly 100 kilometers from the Iran–Iraq border. He is the only one of his eight siblings to have left Iran for the U.S.

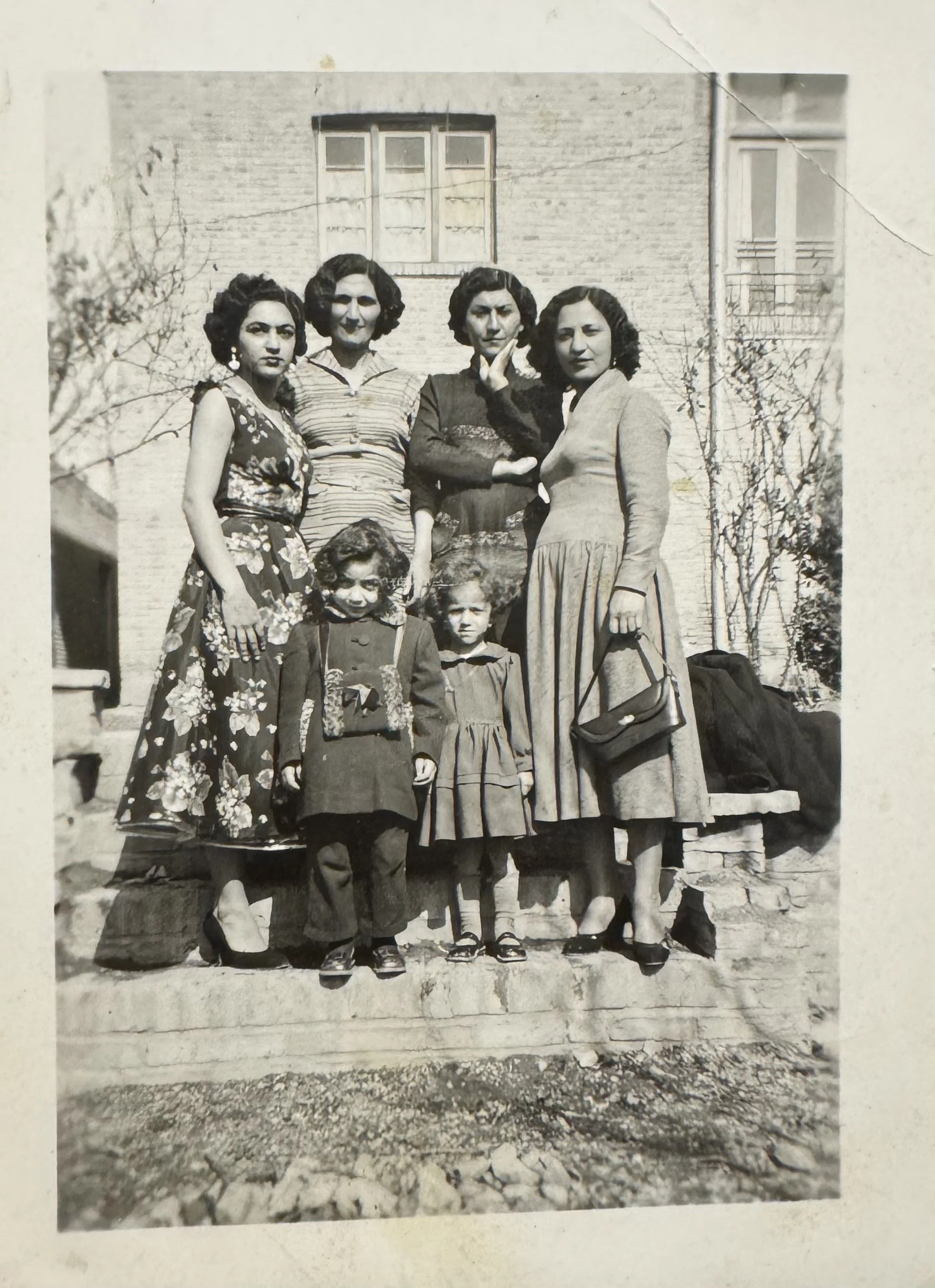

A photograph taken in 1960s Tehran, from a family album belonging to Iranian-American Anoushé, who asked that her last name be withheld. Photo courtesy of Anoushé

When they first heard of the bombings, Anoushé was staying with her parents at their home in Maryland, and she watched as her father scrambled to call his siblings. He was finally able to get in touch with them via video call the day after the first strikes, and they watched as Anoushé’s aunt, wary of government wiretapping, verbally denounced the Israeli strikes while dancing on the screen—a covert sign of a desperate giddiness that something, anything, had been done to target the theocracy. It was confusing for Anoushé, who was terrified for her family. But, she said, there was a part of her that understood.

“[My aunt] has been alive long enough to remember what life was like before the Islamic Republic took power. That generation lives with tremendous loss and nostalgia,” Anoushé said. “I’ve heard my uncles say in the past that they wanted some kind of attack or intervention to get the present government out, which I always thought was crazy. But looking at it now, it just sounds like a lot of desperation.”

Anoushé felt unmoored watching her father’s devastation after the attacks. When on June 16 the G7 issued a joint statement of support for Israel’s attacks, calling Iran a source of instability, her father talked about not going into work the next day, then about wanting to quit altogether. He was caught in a surreal maelstrom of grief and anger, and Anoushé was shocked to see the change in this normally sweet and unflappable man.

“It is so painfully apparent that the people who have the most power are putting everyone in danger,” Anoushé said. “We see this with the United States, and Western hegemony, and white Americans and Europeans—all being able to call the shots for communities and nations so deeply affected by climate change and colonialism and internal conflicts that they’re only facing because of what the Western world has previously done in their country… It’s like this unending nightmare of violence from outside.”

And though Anoushé wishes for the reprieve of hope, even if temporary, it feels increasingly impossible. “We all know Iran is alone in this fight. And we all know the U.S. and Israel and the British are going to work together to make sure of that.”

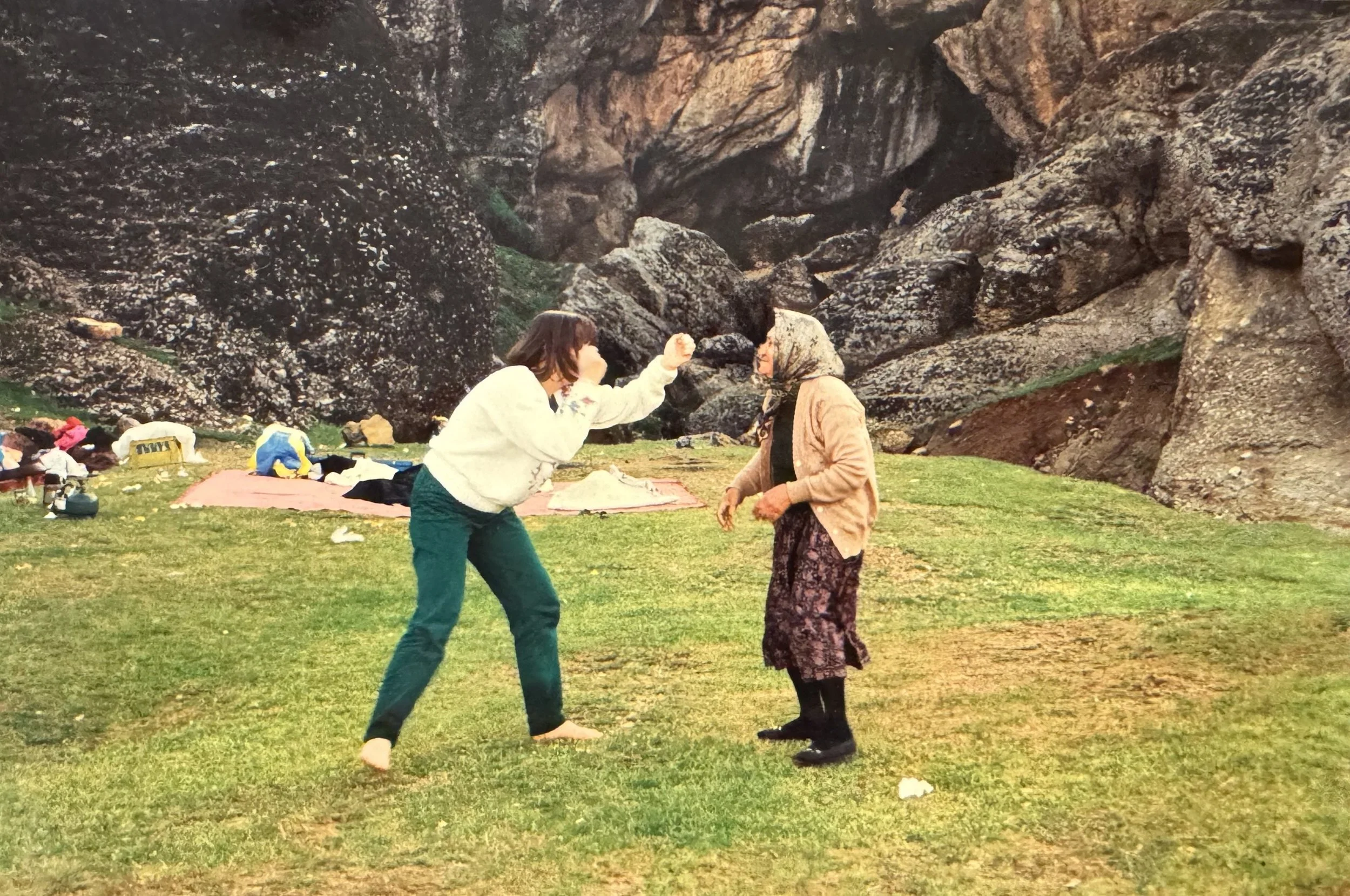

Anoushé’s mother play-fights her Persian grandmother during a family picnic in Iran’s scenic Lorestan province in the 1990s. Photo courtesy of Anoushé

Negar Ghasemi, a pianist and composer, was born just outside of Tehran and has lived in Philadelphia since 2017. Her father, grandparents, several uncles, stepmother and two stepbrothers have all stayed in Iran. She has described the latest period of escalation as paralyzing, especially following the daily internet blackouts stifling communication from within the country. “Pain is always with you,” she said. “I have a lot of heaviness, a lot of trauma on my shoulders.”

When she first called several friends and family members in Iran, she found their responses to be almost defiantly optimistic. ‘This is the cost we have to pay,’ said one friend, who Ghaemi prefers to keep anonymous due to safety concerns. ‘We’re hopeful and happy, because this is a chance we might not otherwise have,’ the friend said. Ghaemi added her own perspective: “If Iranians are crying, it’s [not always] because Israel attacked them, but also because they had to pay this price because the Islamic Republic is their regime.”

Ghasemi, too, is hearing a multiplicity of reactions. She is aware of those arguing that overthrowing a government is the duty of the people, not an external power. “When more radical thinkers disagree with them, they are accused of not being sensitive or having empathy,” she said. But she also sees this moment as a historic opportunity for increased internal resistance. And though Ghasemi struggles with America’s unchecked support of Israel and its arguably inevitable engagement in Iran, she is reminded of an idiom in Farsi that describes how Iranians must choose between the bad, the worse and the worst. “When deciding between worse and worst, America is probably on the ‘worse’ side.”

It’s a cruel kind of mathematics that pinpoints the helplessness Anoushé and advocates like Sanaz Yaghmai wrestle with daily, underscored by brutal truths. Yahgmai recognizes, for example, how escalation provides the Iranian regime with a distraction from its intensifying oppression, surveillance, kidnappings and torture, further exacerbated by their internet blackouts. Iranians and Iranian-Americans are no strangers to this “our-greatest-enemy-is-the-enemy-within” mentality.

And if attacks by Israel and the U.S. weaken the despotic ruling power, there are the unavoidable questions of the cost: What kind of trauma will the bombing survivors be left with? What about the political prisoners—journalists, academics and activists devastated by the Islamic Republic’s rule and subjected to a wide range of human rights abuses—who died in the bombing of Evin prison in Tehran, one of the Islamic Republic’s most infamous detention centers? What about Benjamin Netanyahu’s cruel weaponization of the Women Life Freedom movement that so inspired activists like Sanaz Yaghmai? And what about the destruction of Iran’s extraordinary artistic and cultural heritage resulting from Israel’s imprecise ‘precision attacks’?

Motorcycles line the street in Khur, a city in eastern Iran. Photo: Sanaz Yaghmai

“I don’t know if the people watching care,” Yaghmai said. “Then again, maybe they are watching but they do not know.” After all, Yaghmai herself has been disillusioned by the tidal wave of media interest she has fielded since the initial wave of attacks, most of which has culminated in reductive sound bytes or the conflation of Iranian grief with Israeli grief over the October 7 attacks. Political agendas often eclipse and invalidate the suffering of Iranian-Americans, further isolating them. According to Yaghmai, many of the Iranian-Americans she works with now also feel disillusioned and hesitant to speak out. She wonders whether Iranian suffering can ever be given the space to exist on its own, separate from a broader context.

After all, the Iranian people are not a monolith, Yaghmai said. They have a right to hope as well as a right to weariness. And they can both mourn the catastrophic suffering and take pride in the beauty of a culture that is either unknown or ignored by Western media. Yaghmai sheds tears for the fragility of her homeland, but also for its beauty. She praises Iranians’ proclivity for poetry, the unfailing hospitality extended by family and strangers alike. “Everyone is family,” she said.

Ghasemi has similar memories of being taken to the park in a stroller by her grandparents, and of sipping orange juice as her family chatted and visited with friends. Her core memories are peaceful ones. There are parties and parks and dances and gatherings.

For Anoushé, who longs for the day she can return to Iran, there are the lasting memories of the sprawling Zagros Mountain range. Of picnics in Alasht, known for its sunflowers. Of once watching a goat pick up a picnic teacup and lift it over its head. Of the ballooning black pants of the nomadic Indigenous Lors people, and of introducing her cousins to Slipknot and System of a Down, dancing together by the fountain in her grandmother’s courtyard.

At the end of the day, all she can say is, “I loved everything about being there.” And she must believe, as she must hope, she will one day be there again.

***

Lauren Abunassar is a Palestinian-American writer, poet and journalist. She holds an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and an MA in journalism from NYU. Her first book, Coriolis, was published in 2023 as winner of the Etel Adnan Poetry Prize. She has been nominated for a National Magazine Award and is a 2025 NEA creative writing fellow.