Art as Resistance | At Philadelphia’s First Muslim Arts Festival, Beauty Is a Form of Cultural Power

By Lauren Abunassar

December 1, 2025

The question of why one should make or celebrate art at a time when the world is figuratively — and sometimes literally — engulfed in flames is not a new one. But it is a complicated one, and it is one CAIR-Philadelphia Executive Director Ahmet Tekelioglu faced more than once while helping plan the inaugural Philadelphia Muslim Communities Arts and Culture Festival. After all, with ongoing genocides in Gaza and Sudan, the rapidly worsening immigration crisis in the U.S. and increasing Islamophobia across the country — which recently led Texas Governor Greg Abbott to declare CAIR itself a foreign terrorist organization — was it the best use of CAIR’s resources to celebrate anything, much less the arts?

For Tekelioglu, the answer was clear: “Our community is more than headlines,” he said. “Our community is beautiful.”

This conviction was deeply embedded in the festival’s programming, which took place at the Temple University Performing Arts Center on November 22. The event was a collaborative effort between CAIR–Philadelphia, the Islamic Cultural Preservation & Information Council (ICPIC)/New Africa Center and Muslim City Fest. Performers included the Modero & Co Indonesian dance, music and cultural group, the Universal African Dance & Drum Ensemble, a tatreez presentation with Palestinian–American Samar Dahleh, Syrian–American rapper and educator Mona Haydar and more. As each of the performers took the stage, the possibility of celebrating beauty as an act of resistance, generosity and deep-seated faith became clearer, as did the restorative and empowering potential of cultural festivals more broadly.

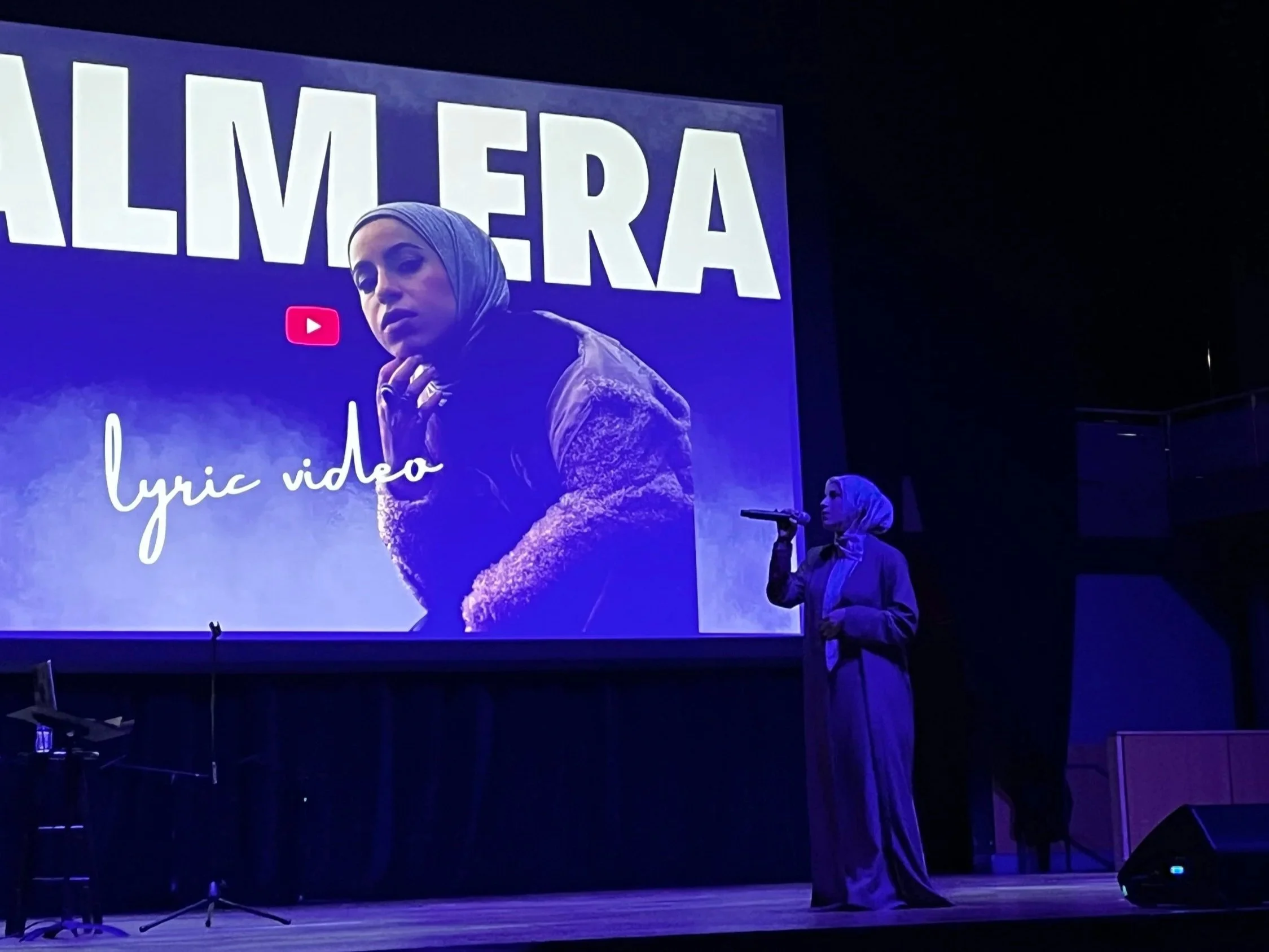

Syrian–American rapper, chaplain and educator–activist Mona Haydar performed several rap songs for the audience, including “Wrap my Hijab,” and an emotional rendition of the Palestine-inspired “A Day Will Come.” Photo by Lauren Abunassar

“The first thing I think about these cultural festivals is that if they help people better know themselves, then they have been successful,” said Dr. Su’ad Abdul Khabeer, who performed at the festival’s conclusion. “When you know yourself, then you can organize and better identify who your ally is, who your accomplices are, who your enemies are.” A trained anthropologist and current fellow at the Institute for Sacred Music at Yale University, Khabeer’s ethnographies on the intersection of Islam and hip hop inform her one woman show, “Sampled,” which she brought to the festival stage on Saturday.

Khabeer’s storytelling sits at multiple intersections; she is simultaneously a documentarian, anthropologist, cultural archivist and community advocate. Performing excerpts from “Sampled” provided a chance to mine the dignity of everyday pain and beauty in community stories that often go unheard.

“Mothers worry about the passing of their traditions, or variants of anti-Black racism in an Islamic school, or the kind of surveillance that the government has done around different groups across time,” Khabeer said. “I’m trying to bring those stories to life on stage, to give people an opportunity to engage with them, to maybe think about them differently, and then also, to do something.”

While Khabeer’s storytelling offered a more magnified view of everyday Muslim life, Ustadh Ubaydullah Evans’ speech on artistic practice in Muslim communities was a way to widen the frame of the festival, exploring art as a spiritual practice, not just an aesthetic one.

“Talking about art and creativity is not secondary or tertiary to Islam,” he told the audience. “It’s primary to Islam. There is a place in Islam for levity. There is a place for celebrating beauty.”

For Evans, beauty is not ornamental; it is formative. Discussions of cultural memory in Islam typically reference religious scholars alone, he said, excluding the artisans, musicians and poets who have shaped its cultural thrust. Evans spoke of his own conversion to Islam in high school, catalyzed largely by listening to hip hop replete with references to the faith. Through this experience, Evans, who serves as the first Scholar–in–Residence for the American Learning Institute for Muslims, challenged the idea that Islamic history is best narrated through jurists and theologians. The arts, he argues, are how Muslims have always spoken to the innate human longing for the beautiful — a longing that exists prior to doctrine and often precedes belief.

“Islam aims to vivify and beautify the entire human condition, ” he said.

Modero & Company was founded in 2011 by dance artist Sinta Penyami Storms, who spoke at the festival of her desire for the group to engage in cultural preservation, bridging historic and contemporary Indonesian culture. Photo by Yessika Penyami

Evans’ speech often gave way to dialogue with audience members; some questioned how to reconcile pre-conversion cultural practices with Islamic traditions, others simply asked Evans to share his favorite Quranic surahs. These discussions underscored many audience members’ desire to find cultural grounding while puzzling through the question of not just what faith one lives but how they live it. And Evans had questions for his audience, too, namely: who is creating Islamic American culture? And how might audience members consider their own role in cultural authorship?

Su’ad Abdul Khabeer’s decision to present her anthropological research in the narrative format of “Sampled” paralleled Evans’ entreaty to consider how the necessity of the arts might lie in their real and tangible utility. “My ancestors were enslaved… We’ve been through the worst,” she said. “There is a lot of art in how we survived in this country. There is a lot of art as a form of release, art as a way of challenging things. When I create art, it’s always within that context… When things break, things can come through.”

Sinta Penyami Storms, founder of Indonesian dance and cultural group Modero & Company, similarly emphasized the importance of cultural festivals in restoring community bonds and enforcing a space to explore diversity within Islamic culture. “We have this motto of unity in diversity,” Storms said. “Indonesia is not a monolith, Muslims aren't a monolith. We come from different traditions and local identities. Different customs. You go to different parts of Indonesia and see how Eid is celebrated. Another part will show you how those people do Taraweeh. But we all live side by side and that’s what [Modero] wanted to show. That harmony.”

Storms was in talks with CAIR about bringing Modero to the festival for over a year. The carefully planned collaboration was a chance to further preserve Indonesian-Muslim culture, for a community that is not always offered a space in Philadelphia’s cultural network.

The inaugural Philadelphia Muslim Communities Arts and Culture Festival, held at Temple University’s Performing Arts Center, was a collaborative effort between CAIR Philadelphia, the Islamic Cultural Preservation & Information Council (ICPIC)/New Africa Center and Muslim City Fest. Photo by Lauren Abunassar

Storms reflected on how the post–9/11 era fed into the fear of expressing Muslim culture in public. Though Storms herself is not Muslim, nearly 90% of Indonesians are, and she recognized how many members of the Indonesian diaspora struggle to feel safe in the spaces around them. Storms believes part of what makes cultural festivals like Muslim Arts and Culture so important is that non–Muslims can learn just how rich artistic expression is in Muslim communities, and the Muslim community can begin to rebuild some sense of belief that their stories, their art and their celebrations matter in a broader cultural zeitgeist.

As guests came and went and audience members continued engaging in question–and–answer sessions with performers, the possibility of an inextricable link between the fight for cultural rights and civil rights became all the more legible. In this sense, the festival affirmed what Tekelioglu proposed at the beginning of the day, before programming kicked off: that Muslim communities are not reducible to crisis or conflict. And at the core of celebrating beauty rooted in history, faith and the everyday labor of living, there is also a way to celebrate unity without uniformity, to recognize that art is not a luxury but a tool for survival.

***

Lauren Abunassar is a Palestinian-American writer, poet and journalist. Lauren holds an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and an MA in journalism from NYU. Her first book, Coriolis, was published in 2023 as winner of the Etel Adnan Poetry Prize. She has been nominated for a National Magazine Award and is a 2025 NEA creative writing fellow.

Al-Bustan News is made possible by Independence Public Media Foundation.