Op-Ed | Beyond Ceasefire: What is Next for Palestine Solidarity?

November 1, 2025

The author has requested anonymity due to concerns about safety and workplace retaliation.

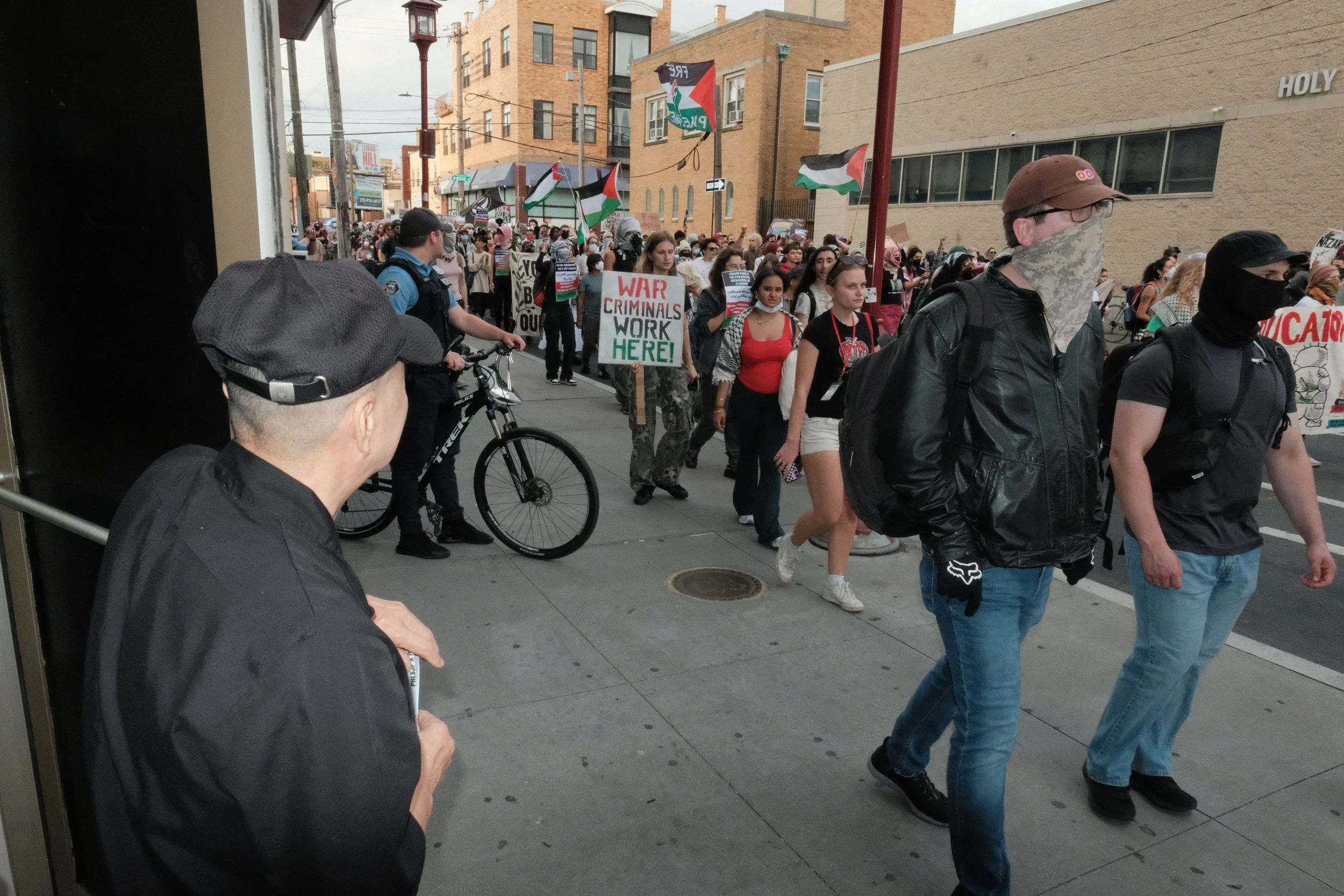

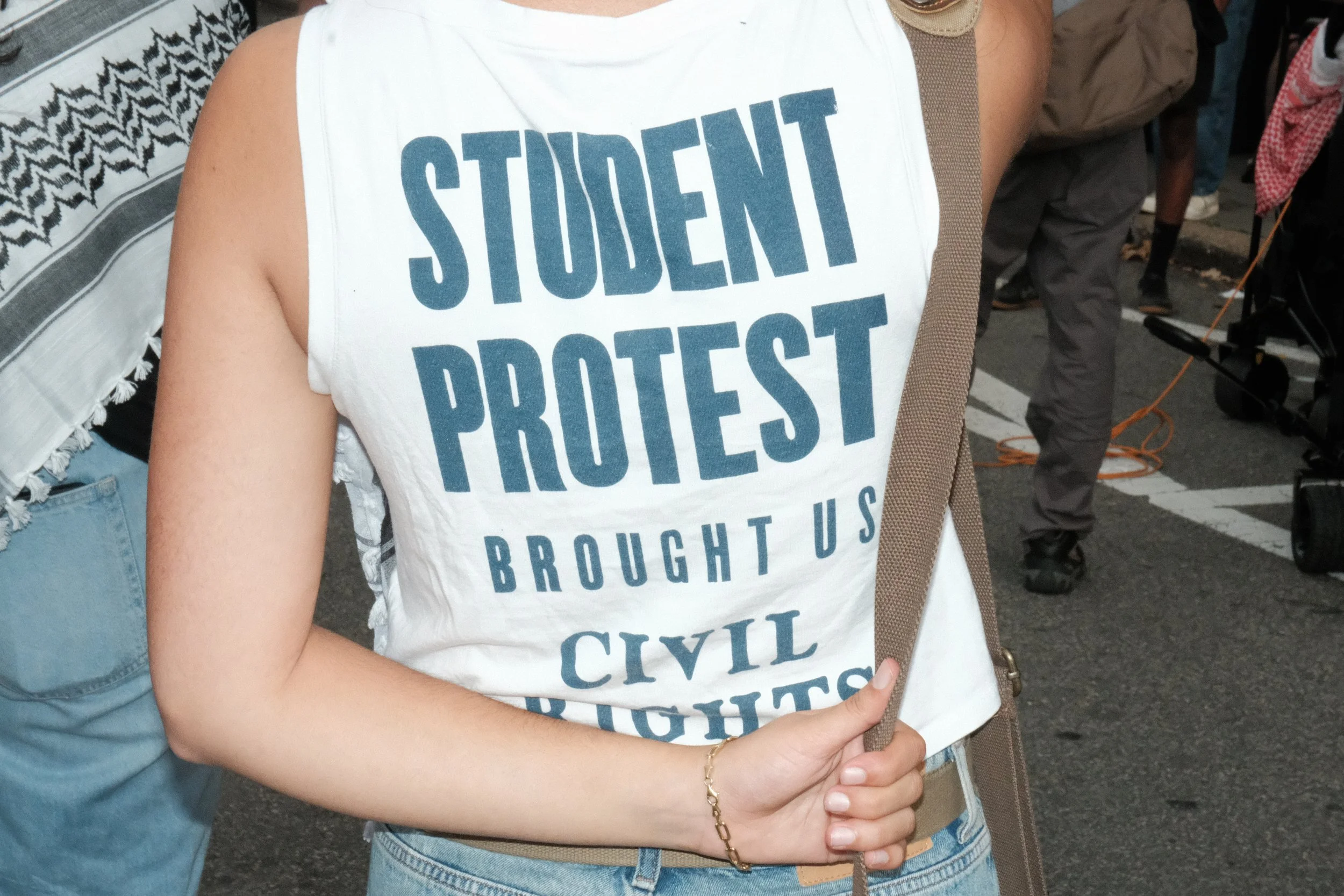

Photos by Ben Bennett

On October 7, 2025, three days before a ceasefire in Gaza was announced, activists gathered in Philadelphia for a protest organized by The Philly Palestine Coalition.

A few weeks ago, hundreds gathered in Philadelphia to mark the two-year anniversary of October 7. Two days later, a ceasefire agreement between Hamas and Israel was formally announced. For many who had spent months watching a genocide unfold on their screens, the news brought relief.

But for Palestinian organizers like Aya, a 29-year-old dance movement therapist in training whose family is from Gaza and who chooses not to reveal her last name for safety reasons, the ceasefire changed nothing.

"Collectively our goal was to ensure that the movement continues and that people do not pat themselves on the back and believe that the ceasefire means an end to their advocacy," she said. Aya has not heard from her extended family in Gaza since December 2023 and does not know if they survived to see the ceasefire.

The past two years witnessed unprecedented mass mobilization, with millions engaging with Palestine for the first time. Now comes the critical question: What happens next?

Within the context of organizing, the problem with ceasefires is that they feel like victory. If the problem is defined as "too much killing," then less killing appears to be progress. But the "quiet" periods between military assaults are also a form of violence. The slow death of siege continues. The grinding dispossession of ongoing settlement continues. The structural elimination continues whether or not bombs are falling.

James Ray, a 27-year-old digital marketer who has organized around Palestine since 2016, warns against seeing a ceasefire as the end goal. "The type of society that we have creates a need for instant gratification, which this ceasefire satisfies," he said. "People tend to fall into the trap of this satisfaction."

The last three weeks have exposed this reality. Israeli forces began violating the agreement almost immediately. On October 18, eleven members of a single family were killed in Gaza. If the structures of settler colonialism remain intact, a ceasefire is a return to "normal" violence, the goal of which is similar to a genocide. This has been the pattern with every previous ceasefire, including those before October 7, 2023.

To understand Palestine through the lens of settler colonialism rather than as a humanitarian crisis alone is to see a fundamentally different problem requiring fundamentally different solutions. Settler colonialism is not a historical event or a policy choice. It is a structure with an inherent logic: it requires the elimination of Indigenous people to replace them with a settler society.

In this light the violence Palestinians face is neither excessive nor an aberration; it is the point of the project. Ethnic cleansing in Palestine began with the Nakba and continues today. The dispossession, military occupation, legal apartheid and blockade of Gaza all exist to sustain this process and create conditions in which genocide becomes inevitable.

For most people entering Palestine solidarity, this framework shift requires confronting not just Zionism but their own national context. "To settle with the settler colonial nature of Israel requires you to settle with the settler colonial nature of the United States, and for most people that discomfort is not something they are willing to sit with," Ray said.

This explains why an anti-genocide framework proves more accessible for a solidarity movement than an anti-colonial one. Genocide can be universally condemned in the abstract. Opposing settler colonialism implicates us. It asks us to recognize that the same logic that enables the elimination of Palestinians enabled the elimination of Indigenous peoples in this country.

This is why the goal of organizing cannot be simply managing violence levels. "It is important for people to … prioritize a long-term robust movement that has a chance of succeeding," Ray said. "It took over a hundred years to free Algeria and other colonized land, and Palestine will be no exception."

In this light, what does solidarity actually require?

First, we must center Palestinian leadership. "Spaces need to ensure that Palestinians are leading the movement," Aya said. This is not a symbolic gesture, but rather a recognition that Palestinians understand the structure they and their ancestors have lived under in ways that even the most dedicated solidarity activist cannot. The strategy, the demands, the terms of liberation must come from those whose freedom is at stake.

Rosa Kurtz, a 25-year-old educator and anti-Zionist organizer in Philadelphia, puts it plainly: "Only Palestinians can define what anti-Zionism is." For Kurtz, who has been involved in pro-Palestinian organizing since high school, this means accepting that liberation will come from Palestine itself. "Our role is to take America's boot off their neck to do so."

Second, we must create political education that reveals the structure so that the millions who came to Palestine solidarity through humanitarian concern can understand why genocide is happening. "It is important to draw people's attention to the connection that Philadelphia directly has to the genocide, like the weapons manufacturers in our city, and to put genocide into the context of occupation," Aya said.

This means organizing teach-ins on settler colonialism, mapping local connections to occupation, creating accessible study groups and hosting Palestinian speakers who can describe their lived experience.

Finally, we must target material support systems through strategic campaigns, most notably Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaigns. The role of international solidarity is not to liberate Palestinians—that work belongs to Palestinians themselves. Solidarity’s role is to help dismantle the material and political systems that enable the colonial structure.

We need a framework shift not because resisting settler colonialism is more radical than humanitarian concern, but because it is more effective. The ceasefire is not the end. The work of ending the occupation has only just begun.

***

Ben Bennett is a Chinese-American visual journalist based in Philadelphia and an Al-Bustan Media Fellow. He is a recent graduate of American University's journalism program, where his coverage focused on underserved communities and the intersection of politics and popular culture.

Al-Bustan News is made possible by a grant from Independence Public Media Foundation.