Art as Resistance | Lebanese Comic-Journalist Tracy Chahwan Wants Her Work to Bear Witness

By Lauren Abunassar

August 1, 2025

Art as Resistance is a monthly column by Lauren Abunassar, exploring the ways that MENA–SWANA artists and performers are defying erasure with socially engaged art.

***

For Lebanese cartoonist, illustrator and comic-journalist Tracy Chahwan, every bomb is an archive. And every archive is a chance to recover and consider the meaning embedded in the things and the people that get left behind.

“With everything that is happening right now, thinking of how [Israel] can destroy a building in a second and destroy any memory that was left behind in a second, this leaves the idea that every bomb that is dropped is also an archive of someone’s life,” Chahwan said. As an artist, she finds herself considering how to offer some record of these sites of erasure.

It’s the question at stake in Chahwan’s comic, “Every Bomb is an Archive,” published in “Revenge #2,” a zine from the Lebanese experimental comics collective, Samandal, which explores narratives of Lebanese and Palestinian resistance and survival. In the comic, Chahwan offers a series of vignettes that move across miles of vast distance. Hand-drawn images of her Teta’s cluttered veranda in Lebanon give way to an Arabic bookshop on 52nd Street in Philadelphia. A dispatch from Gazan academic Mahmoud Assaf gives way to the Museum of Memories in the Shatila Refugee Camp—a small room filled with hair combs, coffee pots and other totems displaced Palestinians were able to cling to and donate to the museum as desperate proof of what they once had and lost.

A page from “Every Bomb Is an Archive,” a comic by Tracy Chahwan in the zine "Revenge #2,” which was published in May by Lebanese experimental comics collective Samandal. All images courtesy of Tracy Chahwan

Chahwan embraces ambiguity over certainty when threading together images like these, writing, “I write this, I draw this. I don’t know what it really means.” But her work is also an unflinching testimony of the power of an image to conjure personal and collective histories.

“The comic revolves a lot around this idea of people who can’t let go of things because they went through something traumatic like war,” Chahwan said. It’s a theme she’s grappled with in multiple contexts, including her published work in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Middle East Eye and VICE Arabia.

In May, she helped launch “Revenge #2” at Philadelphia’s Studio 34, which also hosted her first solo art show, “Alien of Extraordinary Abilities,” featuring over a decade of her work. At the launch, she did a live drawing performance that was emblematic of how often she defies the assumption of drawing as a solitary act. Though she once had dreams of becoming a rock star, Chahwan has fused her love for music and performance with her love of drawing. She spent much of her early career illustrating band posters, establishing community in the Beirut art scene by performing similar live drawings at concerts. The event at Studio 34 could be seen as a return to those roots, and an embrace of art as both a catalyst for community-building and a product of it.

“[Art] is always a way for me to process things,” Chahwan said. “Especially now, since, in the last five years, a lot of people have had to leave Lebanon. We’re all over the world so no one really feels at home anymore. Even when we go back to Lebanon, it’s changed a lot. I think everyone is a bit confused and eventually, it’s like, okay—community definitely helps.”

Tracy Chahwan in Beirut, around 2015

As a self-described “stray artist & cartoonist,” finding her way to West Philadelphia was something of an accident. On her way to a comics-focused art residency in Angoulême, France, Chahwan took an impulsive detour to visit her partner in Philadelphia for a month. It was 2020. And as most stories about 2020 go, Chahwan found her plans sudden casualties of a pandemic she had underestimated. Soon, she was marooned in the U.S., left to consider multiple unfolding crises, big and small, at once: her French residency was cancelled, the pandemic only worsened, and the economic crisis in Lebanon became a full blown catastrophe with the Port of Beirut explosion in August 2020.

“A lot of heavy stuff,” Chahwan said. “So I was like ‘Okay, I don’t know what to do with my life. Maybe I’ll just stay here.’” She had never even been to the U.S. before.

Today, she is more or less settled in, even though adjusting to the more “insular” American art scene has been tricky—especially for Chahwan, who describes her own genesis as an artist as punctuated by moves from one art collective to another.

In Beirut, she was enmeshed in the lively comic scene and collaborated with Samandal and Zeez Collective. She participated in the Beirut Groove Collective and formed deep ties to the Lebanese music community. Even before this, Chahwan found a home in the artistic community forged by the Russian-trained painter she studied with when she moved to Cyprus with her mother, who bought her some of those first influential painting classes that started Chahwan daydreaming about a career in the arts.

in Beirut, Chahwan found opportunities for artistic collaboration and formed deep ties to the music community. Above: Chahwan’s posters promoting a performance series in Beirut. Below: The artist’s hand-drawn LP covers

Both of Chahwan’s parents were artists; her late father was a self-trained painter, poet and cultural journalist and her mother was a journalist-translator who read her father’s poems in the newspaper long before she met him at a literary party in Beirut. They surrounded their children with European comics. With art as her guide, Chahwan was able to more easily tune into three different languages and cultures as she moved between Lebanon, Cyprus and life in a French school. Collaboration and art–making felt like a radical act.

Having created visuals for protest signs and T-shirts for Lebanon’s 17 October Revolution in 2019, Chahwan began considering how her cartoons could take on more reportage. The Nib, a political satire and journalism platform for journalistic comics, was like a beacon guiding her toward new possibilities. Since then, Chahwan has developed projects that take a comic-based look at everything from detainment in Guantanamo Bay to the evolution of feminist movements in Lebanon.

“In the past few years, the pieces I’ve done have been a bit more reflective and trying to make sense of things,” Chahwan said. “The [artmaking] has been necessary, if not helpful, in doing that. Still, it’s very hard to write something serious or smart or sensitive about such heavy subjects. You don’t want to just write propaganda. Even if it’s good propaganda.”

As much as Chahwan’s work has been a tool to get closer to what she wants to say, an act of personal meaning-making, it’s also an offering to others. She often reflects on how comics can make the news more accessible, more interesting. Even more human.

But there are also the questions Chahwan must ask of herself and her work more frequently now. Namely: How do you deploy humor when your work is also navigating catastrophe? And how do you reconcile with an unending onslaught of brutal images on the news when you are an image-based artist?

“Nidal’s Story,” for which Chahwan created the visuals, was published in 2018 as part of the comic “Where to, Marie?: Stories of Feminisms in Lebanon.” Script by Bernadette Daou & Yazan Al-Saadi, English translation by Lina Mounter

“I feel like the overload of the images we see [of conflict and war] reach the point where it’s kind of capitalized on. So, the pieces I’ve done were much more like a slow burn,” Chahwan said. This is a sentiment deployed in “Every Bomb is an Archive.” She writes: “The war continues in Lebanon. I have developed a strange unconscious habit of taking random screenshots of bombings.”

It is an earnest and poignant confession that reflects not just Chahwan’s self-described “slow burn,” but also her efforts to undermine any illusion of distance. Gaza is not as far as it seems. Lebanon is not as far as it seems. And the impact of past wars looms as large as the impact of present ones.

Chahwan recently completed a project with her mother exploring this idea, reflecting on the 50th anniversary of the Lebanese Civil War. Having grown up in the aftermath of the war, the project felt like a way to understand its impact more. Collaborating with her mother added another layer of meaning. “This generation that went through the Civil War in Lebanon, they’ve been through crazy stuff. Stuff we can’t even imagine anymore,” Chahwan said. “And they have a lot bottled up. And a lot of stories. They kind of—not ‘moved on’—but had other things to do. My mom had to raise kids. She had to get a job that made money.”

So what happens to those stories, those memories, when life goes on? Chahwan has often encouraged her mother to return to writing, even to develop her own book as she nears retirement. According to Chahwan, her response has always been some version of, “I don’t want to be one of those people who writes about the war.” And Chahwan’s response has always been some version of: “Okay, but you lived through it.”

The insistence on storytelling as testimony of survival, and of survival as a defiant act, is a vibrant throughline in much of Chahwan’s work. She believes in allowing people the opportunity to just make art about their daily lives—to show they have a right to these lives, to humor and to beauty, unpressured to constantly connect back to the impact of conflict. But she is also keenly aware of the importance of allowing survivors to speak for themselves.

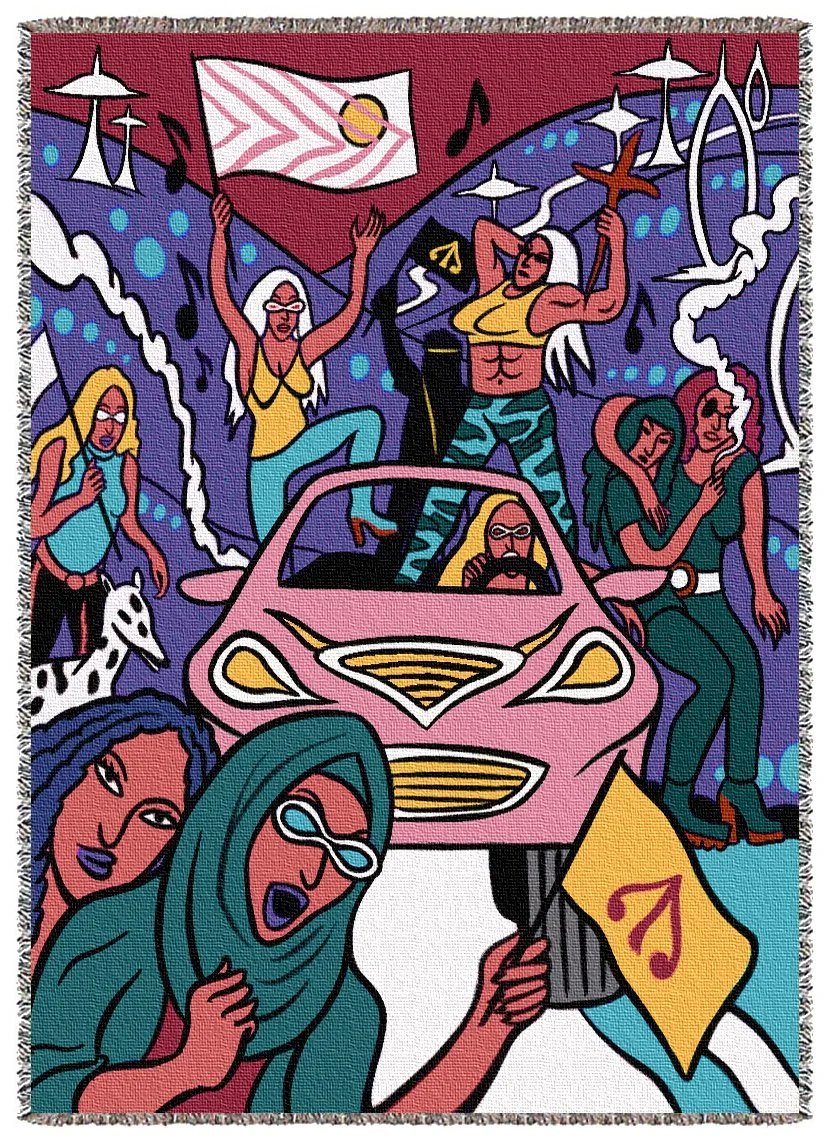

In 2023, “Resembling Resilience,” Chahwan’s series of woven jacquard blankets, was exhibited at Dubai’s ICD Brookfield in a group show titled “Do Arabs Dream of Electric Sheep?”

In Philadelphia, Chahwan joined efforts with La La Lil Jidar, an artist and activist collective with similar aims. The collective is dedicated to using photographs in combination with firsthand testimony from Palestine to counter Israel-biased reporting and provide insight into life behind the apartheid wall in the West Bank. They also most recently exhibited at Studio 34. For Chahwan, it was a reminder of the community-based instincts embedded in Mediterranean cultures. “I’m not really interested in being just an illustrator at home alone,” she said.

Still, today, Chahwan sees cartoonish absurdities all around her. “I feel like in the U.S. and in Lebanon, there is something very violent in the air all the time,” she said. She tries to embrace humor as a kind of coping mechanism. But the parallels between her homeland and her home are increasingly undeniable. She jokes: “Both Lebanon and the U.S. have this horrible state that just wants to destroy you all the time. So I was telling my husband, in a way, I kind of feel more at home here than I feel in socialist Europe.”

It’s a depressingly funny observation. But Chahwan doesn’t exude any sense of resignation or pessimism in conversation. She laughs often. She continues to make plans for future projects. And she seems to model the possibility that art can be both beautiful and functional, capable of reflecting some truth about history, culture, identity and suffering. In a time where the erasure of a people is a risk, making something, again, becomes a radical act of defiance.

If a bomb is an archive, art can be a vehicle that helps one witness it. It’s an important possibility when, at the end of the day, Chahwan is all too aware of a simple truth: “We’re all, I think, a bit homesick.”

***

Lauren Abunassar is a Palestinian-American writer, poet and journalist. Lauren holds an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and an MA in journalism from NYU. Her first book, Coriolis, was published in 2023 as winner of the Etel Adnan Poetry Prize. She has been nominated for a National Magazine Award and is a 2025 NEA creative writing fellow.